Intense eyes peer out from under white, bristly eyebrows. The look is hard to interpret: wary and suspicious? resolute? resigned? defiant?

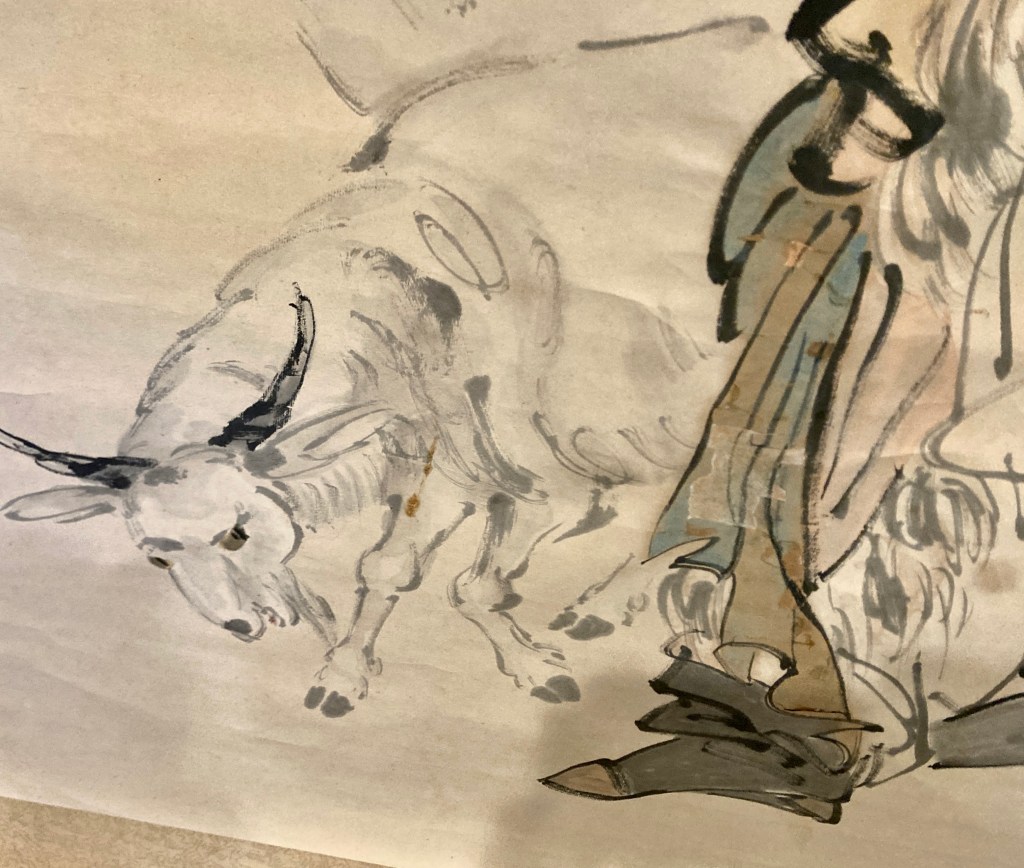

Beard and mustache blend into one white stream, flowing down cheeks and spilling onto the front of his tunic. He leans on an insubstantial staff, barely sturdy enough to bear his weight. It’s a strange-looking rod bedecked with tufts of fur and red ribbons.

His robes reflect the colors of the desert – ocher and pink. The large, loose folds wrap the old man in warm layers. A shapeless hat sits atop his head. The floppy leather boots are well-worn.

Around him are several shaggy, horned animals. The man and the beasts tolerate each other.

This painting of Su Wu Tending Sheep, by Chinese artist Ni Tian (1855 -1919,) was left to me by my dad. The near life-sized old man now gazes out from my bedroom wall. I like to think that he’s looking out for me.

Su Wu is a Chinese historical figure who lived in the first century BCE. Emperor Wu of the Han Dynasty dispatched him to liaise with the Xiong-nu, a fierce barbarian tribe in the extreme northwestern part of China. Some historians have postulated that the Xiong-nu were tribal relatives of the Huns that brought down the Roman Empire. The staff that he clutches is his emissary staff, a sign of his office.

Instead of accepting the liaison, the Xiong-nu took Su Wu prisoner. They banished him even farther west where he was to herd sheep. He spent nineteen years in the desert regions near the Silk Road and reached Lake Baikal in Russia. Legend has it that he was given only male sheep, so that he couldn’t get milk or lambs. Nonetheless, Su Wu remained fiercely loyal to the Chinese Empire and was eventually rescued.

Su Wu is as famous to the Chinese as our Wild West heroes are to us: Wyatt Earp, Bill Hickok, Billy the Kid, Annie Oakley. Mulan, of Disney fame, is another Chinese frontier hero.

When we in the U.S. say “frontier,” we think of the American West. But the Chinese frontier stretched along the Great Wall in the far north and west of that country. The Wall was an attempt to keep out the “barbarians.”

Similar tensions existed along the borders of both the Chinese and American frontiers. The dominant culture in each case, (that is, the Chinese and the Anglo) was agricultural and sedentary. But beyond those frontiers, nomadic horsemen dominated the landscape. Ethnic differences accentuated the cultural friction in both cases.

Starting at the end of the 19th century, Americans besieged by the quick pace of industrialization and modernization turned to romanticized stories of the Old West in books, and later, in movies and on TV. American artists, such as Frederick Remington and Charles M. Russell, depicted action scenes of cowboys, bison, cavalry riders, and Indians. Americans wanted to harken back to “those thrilling days of yesteryear.”

At the same time, Chinese people were feeling nostalgic for their frontier past. It was an escape from the monumental upheavals happening in all areas of Chinese life. In the second half of the nineteenth century, the Chinese imperial government made concession after concession to Western powers due to their military weakness.

For example, foreigners were not subject to local Chinese laws. The British and the French carved out enclaves in Shanghai that flew their flags. “Unequal treaties,” opium, nightclubs, jazz, and capitalism disrupted all levels of Chinese relationships and expectations. These changes happened most quickly and extremely in the port cities, and most notably in Shanghai.

A Chinese mercantile class sprang up to interact with the Westerners and Japanese. These newly rich Chinese, as much as they profited from their financial dealings with the foreigners, were also uneasy with the rapidity and the direction of societal change.

Artists flocked to Shanghai to cater to this new Chinese mercantile class. Ni Tian was one such artist. Chinese frontier art depicted a romanticized view of Chinese at the barbarian border: women in exotic clothes, such as cuffed pants for horseback riding; soldiers in ancient costumes (like those on the terra cotta warriors); horses with and without saddles, with and without riders; and of course, Su Wu.

These artists were susceptible to Western influences. They did not stick with the traditional, “literati” painting style with vast landscapes of mountains and mist. If there were people in these earlier paintings, they were invariably tiny and without distinctive faces or personalities.

The artists in Shanghai were called the Haipai, literally, the Shanghai style or Shanghai bunch. In the way that the word “Impressionism” began as an insult, Haipai was a derogatory term given them by more orthodox painters.

The Haipai incorporated Western painting sensibilities that they themselves were exposed to in that international city: the bold strokes, the prominence of the individual as subject, the emotive expression in the face, the sense of perspective.

My dad was born in Shanghai in 1920, just one year after the artist Ni Tian’s death. In Dad’s youth, Shanghai was a wide-open city, known for commerce, foreign enclaves, Art Deco architecture, fabulous wealth, gangsters, and decadence. It was divided into the International Settlements ruled jointly by the British and the Americans, the French Concession, and the Chinese City.

Dad’s family was well-to-do because of his father’s construction company. From the get-go, he was exposed to the heady mélange of cultures in the “Paris of the East.” He lived in the Chinese City. He could speak French. He played soccer and joined the Boy Scouts. His family was Catholic.

Mom was born and raised in the French Concession. Her family was also staunchly Catholic. (Side note: Chinese (+) Catholic = many, many children.) Her huge, extended family was firmly entrenched in that mercantile class. Many of her relatives had extensive dealings with the foreigners and were fabulously wealthy.

Mom and Dad met as medical students at Shanghai’s Aurora University, run by French Jesuits. Their classes were conducted in French. They rode to school on bicycles that had kerosene lights on the handlebars. Theirs was a love match, a relatively modern idea.

One day Dad took Mom to the movies. Pictures of Shanghai show gorgeous Art Deco theater buildings. I don’t know what their tastes in movies were, but a Wikipedia list of 1940s Chinese movies included several “historical/adventure” movies, among them, Su Wu Herds the Sheep. Yes, our Su Wu.

At this point, Mom would interject that she itched all over because the cushions were infested with bed bugs. I asked Dad how did they ever get rid of the bed bugs? He replied, “DDT.”

You get a feeling of how cosmopolitan Shanghai, and my parents, were. I didn’t get a sense that they worried too much about where their cultural influences came from.

Dad left China for America in 1948 when he was just twenty-eight years old. Throughout the rest of his long life in America – he died at ninety – he loved Chinese art. As soon as he had the money, he became a collector.

Su Wu Tending Sheep was one of Dad’s acquisitions. I think he had a special place in his heart for this style of painting that originated from his hometown with its Eastern and Western influences.

As someone who dabbles in watercolors, I am awed by the courage and the skill to make huge, foot-long brush strokes. Some of them finish to a fine point. Others show the bristle marks as the paint runs out. Once you lay that ink down, there’s no going back! Su Wu’s entire outfit is depicted in a half-dozen lines. The ambassador’s staff is authoritatively rendered in three sure verticals. It’s a marvel that you can’t tell where his robe ends and where the sheep start.

Most of all, I love the way his face is rendered. This is a face of someone who has suffered.

Su Wu’s captivity dragged on for nineteen years, an unthinkably long time. Then I think, the Chinese Revolution and the US response to it kept Dad from returning to China for twenty-eight years. By then, his mother had died. Time passes and there are losses.

Time passes for me too. It’s taken me a decade to get the picture on my wall. The painting had a hole in the knee. The hundred-year-old paper was so brittle that every time I unrolled the scroll, another little piece broke off. I scraped up tiny beige corners of paper into an envelope for safe-keeping.

I didn’t know any art conservators. I didn’t think the St. Louis Art Museum would want to bother as the painting was appraised at a low monetary value. (I just happen to love it.) I sat out Covid without making any attempts to get it fixed. It crossed my mind that, rather than letting it sit, I could just use scotch tape, like I did to posters in college.

Then, last year, I called the St. Louis Zoo to buy tickets for Garden Aglow, a special show of huge lanterns shaped like animals. The show originated from China, of all places. My grandsons were going to be in town, and I thought they would enjoy it.

When I gave my name, the Zoo customer-service person recognized me. I had been her doctor years ago. She told me that another of my patients, John Martin, was a framer and … an art restorer! Right in South St. Louis, about a mile from the apartment where our family lived when we first came to America.

And John did it! His repair is a subtle blending of lines, shapes and colors. Thank you so much, John, for accepting the challenge and using your creativity to fix my painting. Like Ni Tian, very bold!

Su Wu now watches over me as I sleep. A loyal and steadfast guardian.

And what do I see? A gorgeous work of art. An artistic goal to aspire to. A reminder of my Chinese heritage. A musing on exile and the brevity of life. Gratitude for lucky coincidences. And most of all, a remembrance of my dad.

Tell me: What object has layers of meaning to you and no one else?

3 replies on “Art is Long, Life is Short”

Please display if you can. It’ll bring you joy.

LikeLike

A lovely essay on your treasured artwork and this history it represents related to your parents! I’m not sure I have something of quite such historical meaning, but with the recent death of my sister, I have inherited several paintings painted by my Uncle Howard (works that primarily feature trains traveling across different landscapes), as well as a portrait of my great grandmother on my mother’s side, whom I never met. I am not sure what will happen to these artworks once I’m gone (a thought that saddens me), but for now, I have them for safekeeping and hope to display one or two of them at a time.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Cathy,

i so enjoyed reading this blog as I looked at that wonderful painting. You are an amazing story teller as you also teach about history and culture. Thank you my friend

mary dee

LikeLiked by 1 person