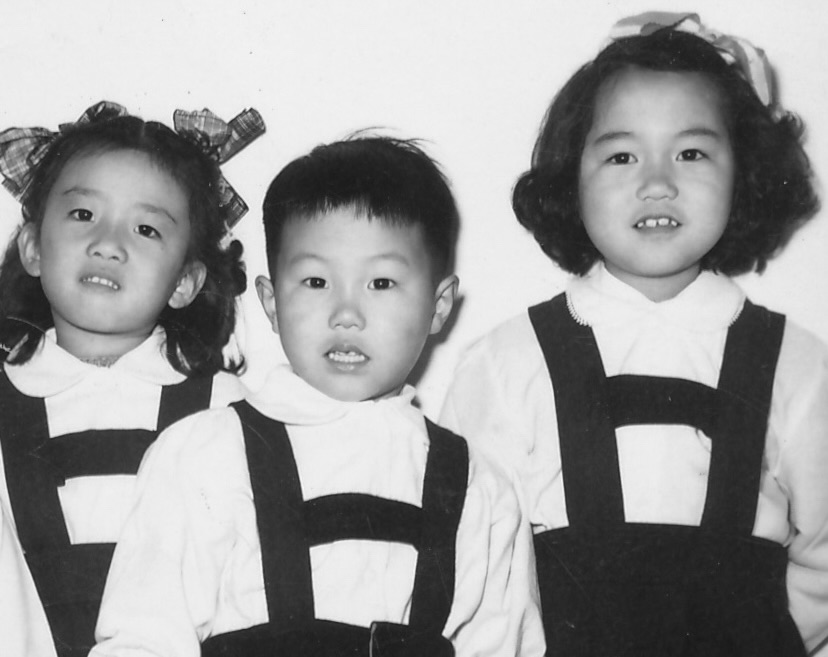

Sure-footed as mountain goats, my sister Long-Long and I picked our way down the steep, narrow dirt path that typified much of Hong Kong’s terrain. Rough-cut slabs of stone, some cracked and dangerous, bridged over ravines. I was seven. Rose was a year younger. We were on our own, on our way to catch the public bus to get to school.

We lived in a compound fancifully called Jade Flower Garden, an enclosure containing a couple of two-story concrete buildings, a tin-roofed house, a gazebo, and a water well. Shacks and vegetable plots lay scattered beyond the compound’s fence. Children and chickens ranged freely.

Mom, Grandfather (her dad), Long-Long and I shared a second-floor apartment with two other families. The roar of airplanes taking off and landing at nearby Kai Tek airport reverberated off the concrete. The compound was in an area of Hong Kong called Diamond Hill, a district full of refugees from the Chinese mainland – like us. Most of the refugees entered the British Crown Colony illegally – like us.

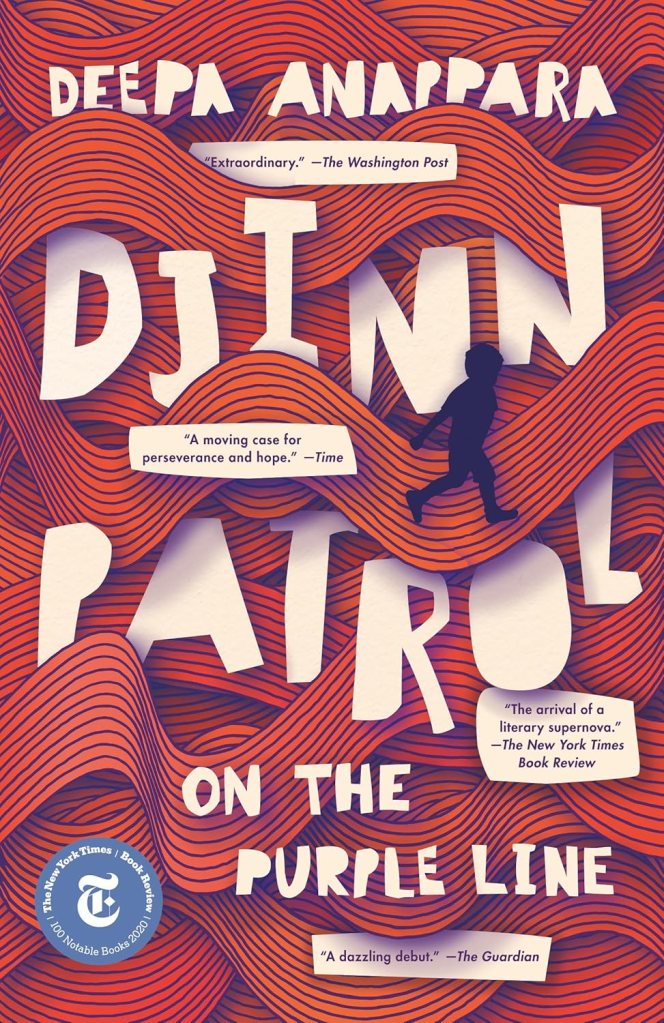

Deepa Anappara’s 2020 novel Djinn Patrol on the Purple Line has sparked these memories of my 1950s Hong Kong childhood. Jai, a nine-year-old boy who lives in a present-day Indian slum, narrates the novel. Anappara’s vivid descriptions awoke my memories of growing up in a Third World setting.

Jai, his sister, and his friends all face limitations to their happiness and their hopes for the future. Jai’s family of four lives in one room. Jai and his sister sleep on a mat that gets pushed under the bed during the day. They pay to use communal toilets. His mother and sister haul water in pots and jerrycans to store in plastic barrels outside their door. The choking, stinking smog darkens the day. Garbage litters their alleys.

There is never enough money. The basti (slum) kids take jobs to help the family. Jai washes dishes at a teashop. Omvir delivers laundry for his father. Faiz has multiple jobs.

Hunger stalks the kids. The book describes many longed-for foods. Jai says, “I can smell the roasted peanuts and the steaming sweet potato cubes dusted with masala and lime juice that hawkers sell from their carts and baskets.” He daydreams, “I wish we had some meat to put in the dal… When I’m grown up and rich, … I will eat mutton for breakfast, lunch and dinner.”

Clothes must last forever. Jai’s Ma says, “only rich people throw clothes away when there’s still life left in them.”

Our place in Hong Kong didn’t have running water either. A tiny, barefoot woman hauled water hand over hand from our well. She carried two buckets at a time up the stairs and tipped the water into a stone tub by our door. Mom covered the cistern to keep bugs out.

My mom, sister, and I slept on one bed in our room. Grandfather slept behind a curtain Mom hung in the dining room. The two other rooms in the apartment went to Mrs. Chang, who was childless, and Mrs. Yuan and her two children.

Neither the Yuan kids nor we remembered our dads. They had gone to America to study and were stranded there because of the Chinese Revolution. Our mothers ardently wished to join their husbands in America.

Unlike Jai, our family wasn’t always poor. But we abandoned everything to escape from China. The change from living in a three-story villa to sharing an apartment with three families must have devastated Mom and Grandfather. We kids didn’t notice much because, even when we were rich, frugality was a virtue mom lived by. She added water to stretch the ink for writing Chinese characters. We squeezed tiny dabs of toothpaste onto our toothbrushes. Heaven forbid I should break a glass, lose a shoe buckle, spill food.

What the basti kids and my Hong Kong childhood had most in common was our acceptance of our life circumstance. No self-pity. No feeling sorry for ourselves. We might have pitied our parents a bit – Jai’s mom working for the mean “hi-fi” madam; my mom missing Dad – but never ourselves.

We made do, finding fun where we could. Jai and friends play “night cricket” in their alley using textbooks for bats to smack a small plastic ball. Jai’s sister grabs every opportunity to train for competitive running. Jai’s fascination with TV detective shows leads him to investigate a classmate’s disappearance.

Some of our games were impromptu, like, who could stand the longest on the upper level of a jolting double-decker bus without holding on. We played pick-up sticks, jump rope, and a Chinese – and harder – version of Jax.

My favorite game called for wrapping and unwrapping your legs along a six or seven-foot stretch of looped rubber-bands. Two players held the ends, changing the height of the rubber-band rope (ankle, knee, waist, shoulder, ear) while the jumper does her little dance. There’s a rhythm to it: hop wrap, hop other leg wrap, hop unwrap, hop other leg unwrap.

The adults in Jai’s basti are beset by corrupt policemen, Hindu-Muslim tensions, demanding employers, and always, the lack of money. Some resort to drink. Some to religion. Neighbors try to help each other. Everyone pegs their hopes on their children, even if it sounds like scolding. When Jai finishes tooth-brushing, his Ma snaps, “Why are you still here? You want to be late for school again?”

The kids feel the pressure and create ways to cope with parental expectations. They remain quiet instead of hurting the parents’ feelings. When Omvir’s dad proclaims, “I’m doing this for you,” pointing to his run-down laundry stall, Omvir doesn’t have the heart to tell him that he didn’t want to be a press-wallah. His ambition is to be a dancer.

When Jai gets kicked out of class, he not only kept it from his mom, but he built in an excuse. “I turn into the alley that leads to our basti and cough with my hand covering my mouth. This way, if a lady from Ma’s basti-ladies’ network sees me and snitches to Ma about me cutting classes, she’ll also have to say that I looked quite sick.”

To spare feelings or to avoid punishment, the kids keep their parents in the dark. Jai’s reasoning goes, that no matter what trouble he got into, “Ma would never forget. This is why I can’t tell her anything.”

Even at that young age, I sensed that taking care of us and grandfather, getting along with the other families in the apartment, money, and dodging Hong Kong immigration authorities weighed on Mom. Oh, and our education.

As with Jai and his friends, I too had mixed motivations about not telling Mom about my days. I didn’t want her to be unhappy, possibly unhappy with me. I didn’t want to add to her worries. (Mom never hit us. She rarely raised her voice. She quelled anything objectionable with the look.)

So, she never knew about my very first school in Hong Kong – when I didn’t even speak Cantonese yet – where, if you failed nail inspection, you were stood in front of the class as the kids mocked you. She wasn’t aware that, at my second school, St. Theresa’s, the other kids shoved me to the end of the line whenever we queued.

And at our next school, the prestigious St. Mary’s, I sat mute and uncomprehending through every class. Mom enrolled us because the classes were taught in English. She wanted to prepare us for life in America. Knowing no English at all, I never knew what the class was about.

In fact, this would be true again the next year when I attended St. Joan of Arc School in St. Louis.

And I certainly didn’t tell Mom about the sweet-soymilk seller. Sweet-soymilk was a treat. The seller carried his wares in two buckets hanging from a bamboo pole on his shoulder. Dozens of children would run after him. Then he’d put his buckets down and ladled little bowls for us. As you went by to pick up your bowl, he’d run his fingers under your panties. I never went back, but I never told.

Djinn Patrol on the Purple Line reminded me of how complicated growing up was … and is. Whatever the circumstance, each of us had to tough out many sticky situations, and often, alone. It also made me realize how brave we all had to be just to grow up.

Tell me: What secrets did you keep from your parents — whether for your sake or theirs?

7 replies on “Growing Up Is Tough”

Hi Cathy, I hope all of this memoir information will someday appear in a book about your entire life. As I recall, in your last installment, if I may call it that, dealt with your feelings about, among other things, race. You’ve got such a rich selection of life long photographs too which would add to a detailed memoir. Barry

>

LikeLiked by 1 person

Might happen! Thanks.

LikeLike

I love reading these stories of your childhood. You should write your own story!!!!!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Cathy..your memories are so clearly written that I almost felt like I was a close neighbor. Thank you for sharing..you are amazing!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Cathy..your memories are so clearly written that I almost felt like I was a close neighbor. Thank you for sharing..you are amazing!

LikeLike

Cathy..your memories are so clearly written that I almost felt like I was a close neighbor. Thank you for sharing..you are amazing!

LikeLike

Another great review, Cathy!

You are so insightful in drawing insights and memories about your own life from the books you review, whether fiction or non-fiction. It’s a reminder to me that a book isn’t like a potato chip to be consumed and forgotten. The best books provoke mental and emotional connections to a reader’s real life.

I have also read the Djinn Patrol. I, too, highly recommend it.

LikeLiked by 1 person