“Cairo.”

Sister Cathlin, our High School English teacher, pointed to the word she had written on the blackboard and asked, “Does anyone know where this is?”

“It’s a city in Egypt,” I blurted. I burned in embarrassment when she said, “Yes, but … it’s also a town at the Southern tip of Illinois. It’s pronounced KAY-row.” Sheesh, I’ve always hated being wrong.

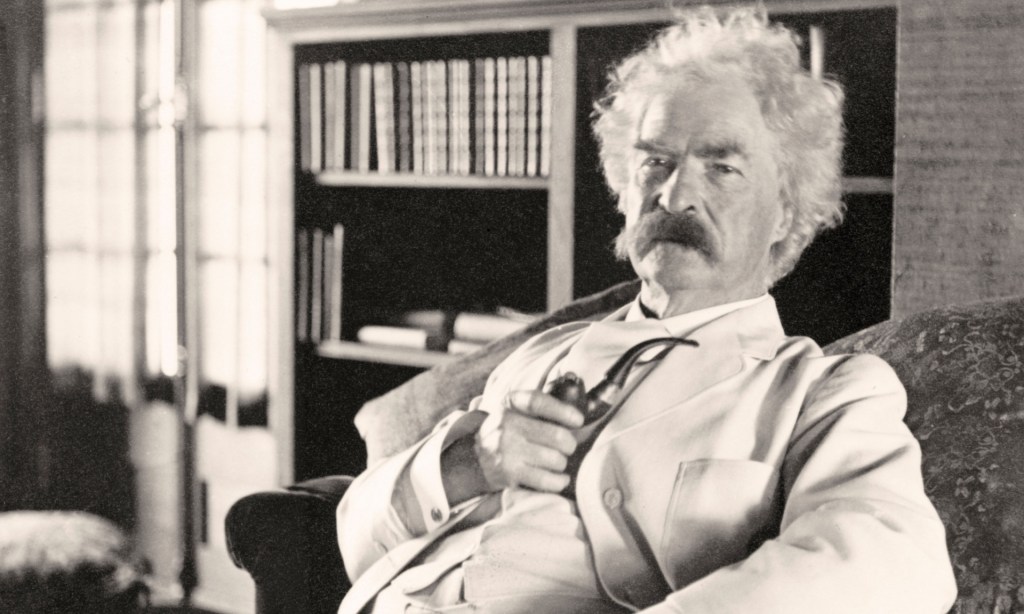

This was Sister Cathlin’s way to take us into Mark Twain’s The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn. We Honors English girls all wanted to get away from homework assignments to raft down the Mississippi. Thanks to Sister Cathlin, we all pegged Huck’s speech about going to Hell rather than betraying his Black friend Jim as the climax of the book. We thought the sections about the Duke and the Dauphin were silly. My teenager’s heart broke when Jim missed his one chance for freedom, his raft drifting past Cairo – and the Ohio River – in the dark.

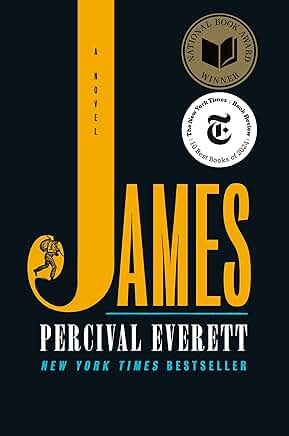

James, the Pulitzer and National Book Award winner by Percival Everett, has been described as the Huck Finn story told from the enslaved Jim’s point of view. But it is so much more. Many of Twain’s characters and plot lines are present, for sure. Everett even captures Twain’s sly, cynical humor in skewering religious hypocrisy and human gullibility, greed, and cruelty.

But I made little connection between the people and circumstances in Huck Finn and my world growing up in the 1950s and early ‘60s. We had no Black neighbors in South St. Louis. Xavier High School for Girls Class of 1965, some one hundred strong, counted three Blacks. And one Chinese: me. I had no framework for understanding “race” in America, from either the Black viewpoint or the White.

But Everett uses these themes as a scaffold to create a new – more complete – narrative of America’s story. James takes place right before the Civil War. American society consisted of one group of people completely at the mercy of another group in perpetuity. What distinguished the groups were skin color and language. Everett shows just how porous these borders are – and how easily crossed.

A “slave” who speaks grammatical English is a source of confusion for the Whites, including Huck. A “slave” who could read and write is almost unimaginable. Skin color is an absolutely unreliable indicator of one’s “race.” (Scientists have discounted the concept of race since sequencing the genetic code a quarter century ago.) Everett shows many instances of misidentification of “race” in both directions, sometimes funnily, sometimes tragically.

Jim’s chronicling of his thoughts, feelings, and actions builds up his self-identity from an enslaved man to free man. Everett uses Jim’s story to create an alternative interpretation of the Black experience. In doing so, he reevaluates the whole of American history.

The Black person, family, and community are sewn into American society as tightly as stitches in a quilt. No longer can Blacks be relegated to Mammy, the butler, or the guy whose only role is to sing “Ol’ Man River.”

I would love to see such a treatment of the history of the Chinese in America. Because, in both cases, there is a bleak history of suffering and discrimination, and then there is the rosier, albeit imperfect, present. James, though fictional, makes the connection between then and now: in the way Jim thinks, in his bearing, in his daring.

Another homage to Twain is the emphasis Everett places on the role of language. Twain wrote the Adventures of Huckleberry Finn in various local dialects to reflect American speech as opposed to Englishmen’s. Everett does a delicious turn on this theme, distinguishing enslaved people’s dialect among themselves versus when they speak with the Whites.

I am acutely aware of the power of language to determine one’s place in society. (And not just because I know all the songs in My Fair Lady.) I have used this ploy, purposely speaking in colloquialisms in my South St. Louis accent to assure that listeners don’t take me for a “foreigner” because of my Asian face. My parents called me Ling-Ling. My classmates knew me as Cathy.

Not everyone takes the hint. Sometimes, my lack of an accent will elicit a “compliment.” “Your English is very good.”

This is a hard review to write. For starters, I don’t want to give away any spoilers. My delight at discovering the twisty variances from the Twain story should be yours to discover too.

Then, I am not Black. I do not mean to offend if I make a wrong assumption. I know this could, likely will, happen if the past is any guide.

Over the years, I have had to revise many initial beliefs about Black people in America. At first, I figured Black people lived in North St. Louis because they wanted to, not because of redlining and neighborhood covenants. I couldn’t understand why stories and movies about Black families, like A Raisin in the Sun, were always so depressing. I assumed police fairness – buying into the “few rotten apples” explanation when a young Black person is wantonly killed by a cop – until Michael Brown’s death and the Ferguson protests. What am I still getting wrong?

On the other hand, I am not White either. I cannot speak to White attitudes from my own experience. I have no forebearers whose mindsets reflect White peoples’ thinking. I have friends whose ancestors were fierce abolitionists, and other friends whose parents played “Dixie” at every turn. What am I getting wrong about White people?

Despite these trepidations, I am writing about James. Because it is a great book. Because I love it.

I also have a special connection. I have lived in St. Louis, on the Mississippi, for seven decades. Over the years, I have seen the power of the river, flooding huge swaths of land, from Iowa down to Cairo and beyond. I have taken pleasure rides on the river, drifting past tangled trees and shrubs not unlike that described by both Twain and Everett. I can understand some of Jim and Huck’s feelings on the river. The river is safety and peace. The river is danger and death.

I have laid eyes on “Jackson Island” from the porch of my editor Laurie’s parental home in Hannibal. Jim and Huck became friends while hiding out on the island from the townspeople.

Ever since reading James, I can’t help wishing that someone would re-cast the Chinese-American narrative the way Everett did for Blacks. Chinese-Americans have often been presented as stereotypes: Hop Sing, Charlie Chan, the Kung Fu guy. In recent years, our jobs and social statuses are less degraded. We are portrayed as doctors, tech geniuses, even crazy rich.

Yet, even when the Asian wins – love, the job, social acceptance, what-have-you – the telling of that accomplishment is from within the framework of White society. We are called the “model minority.” To me, the emphasis is on minority.

Percival Everett’s James opens the door to other writers to reimagine stories of race and society. My fingers are crossed that one of those writers is Chinese-American. I’m not sure what shape the Chinese-American narratives might take. But my heart and head will absolutely know when I find it. Just as I knew when I encountered James.

Tell me: Do you feel like you are a “minority” person in some way?

5 replies on “Jim and Ling-Ling; James and Cathy”

Thank you, Barry. I thought I had put in a reply but I don’t see it. Will you be my promoter?? Haha.

Marilyn Leff asked about you. We’ve been getting together by phone once a week to write.

LikeLike

Aww, Barry.

Wish you were my promoter. I’m not very good at it. Btw- Marilyn Leff asked how you were. She and I try to meet by phone once a week to write.

LikeLike

DEAR CATHY, I think it would be great if you got this published in a literary magazine or as one of your guest essays in the NY Times, or somewhere with a wide readership. It’s so open and vulnerable. Truly.

I was also really impressed by Everette and “James.” I’m happy it has won so many important prizes. I’ve read other reviews too, but yours is by far the best and puts so very much more in perspective, both literally and personally.

Barry

>

LikeLike

I’ll send you a link by email, Susan. Thank you.

LikeLike

Thank you, Cathy! My book group recently discussed James. I would like to send them your review but can’t figure out how.

LikeLiked by 1 person