Every night, the sharp rap of mah-jongg tiles being discarded and the clatter of tumbling tiles being “washed” echoed throughout our small apartment compound. The sound carried as every window was open to let in the breeze in sub-tropical Hong Kong. I was only six in 1953, but I already knew that the native Cantonese banged big mah-jongg tiles on bare tables because they liked their mah-jongg loud.

We Shanghainese are more reserved, dampening the noise with a tablecloth and using smaller tiles. Some of that reserve might be a carryover from having to play on the sly. In Shanghai, and the rest of mainland China, it was illegal to play mah-jongg. (Hong Kong was a British colony.)

Mah-jongg, after all, is a gambling game. Money always changes hands. Even when husband Bill was learning to play, Mom would make him pay up. It was the cost of learning, she’d say.

In addition to the fun of gambling, mah-jongg is aesthetically pleasing. Each tile is smooth and cool to the touch. One surface is etched into multi-colored, geometric forms or Chinese characters. Picking up a piece and running the etched surface over your thumb before flipping it over to look becomes a sensual ritual.

The basic rules of mah-jongg are the same, the way the rules of poker are the same: full house beats flush, flush beats straight, and so on. Let me say here that each mah-jongg group has different rules as to how much each pattern of hands is worth. Again, as in poker, there are myriad variations: “deuces wild” or “Texas Hold ‘em” or “seven-card draw.”

What is important is that the odds of winning change with each variation. The shrewd player adjusts.

***

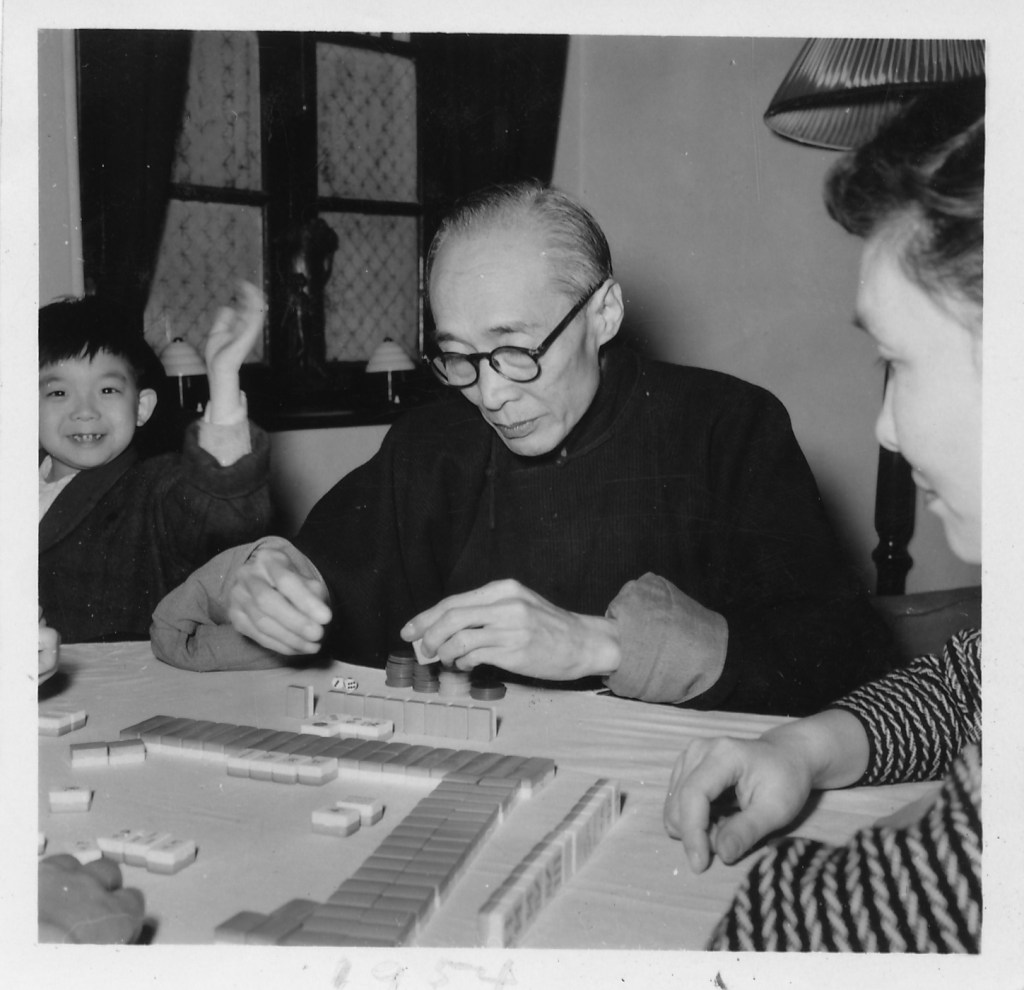

Mah-jongg was a constant in my life. In Hong Kong, the grown-ups in my life – my mom and my grandfather – huddled around card tables with neighbors, relatives, and friends. Or we’d go to other peoples’ homes where mah-jongg was a prominent feature.

Later, when we joined Dad in Saint Louis, mah-jongg continued to be a family affair. Mom had shipped two mah-jongg sets from Hong Kong. Dad built two formica-topped tables. I imagine he did plenty of “carpentry” in the OR as an orthopedic surgeon, but the tables were the only home handy-work he ever did. Mom sewed sturdy white tablecloths with strings that tied to the table legs to make a taut, smooth playing surface.

Once a week, I would come home from St. Joan of Arc grade school to find Mom, Grandfather, close family friend Mrs. Yuan and new St. Louis friend Mrs. Chen hunched at the mah-jongg table. Mrs. Chen breast-fed her son right at the table without stopping play. Everyone drank Chinese tea. They cracked watermelon seeds, leaving little piles of shells in small discard bowls.

Mom allowed my younger sister and me to watch her play. This was how we learned. When we got older, she even allowed us to fill in for her when she had to use the toilet. We plied her with tea.

After college, I planned to spend a year living in Hong Kong and Taiwan. One afternoon, my dad blurted out, “Don’t play mah-jongg with strangers.” It was the only unsolicited advice he ever gave me. He worried that his Americanized daughter, who always thought of mah-jongg as recreation, would be fleeced by ruthless Chinese gamblers.

In Amy Tan’s 1989 novel, a group of Chinese immigrant women in San Francisco named their mah-jongg group The Joy Luck Club. These women reflected on their lives in China, their current situations as immigrants, and on their relationships with their Chinese-American daughters. Then Tan gives us the daughters’ points of view.

The relationship between mothers and daughters showed the usual generational tensions heightened by the huge differences in personal and cultural histories. And yet, mah-jongg connected them. The book begins:

“My father has asked me to be the fourth corner at the Joy Luck Club. I am to replace my mother, whose seat at the mah jong [variant spelling] table has been empty since she died two months ago.”

Since this book came out some thirty-five years ago, for one thing, I’ve gotten that many years older. My mom died in 2015 at age 98. I have no beefs with her at this point.

Also, China, women’s position in America and, most importantly, Chinese-American writing have all moved into the 21stcentury. China changed from a poor country of drab clothes to a place of skyscrapers, bullet trains and many in the “middle class.” Women are now staples of American orchestras, TV news, and to some extent, professional sports.

Present-day Chinese-American writers – Charles Yu, Weike Wang, Ted Chiang, Grace D. Li, among others – have taken writing about being Chinese-American in awesomely original directions.

But mah-jongg plays on.

As Mom and Dad prospered, they hosted dinner parties. Mom spent days preparing the food. The mah-jongg players would come early to play, and then continue after eating. They would snarf up the food in minutes so they could get back to the game. Mom didn’t seem to mind.

Many of the players were graduate students at Washington University. One became the president of Hong Kong University. Another, the Lieutenant Governor of Delaware.

Mom’s daytime mah-jongg group changed with the years. For about ten years in the 1990s, they called themselves The Four Sisters, arranged according to age. Mom was Da Jie, the Big Sister. The others were Second, Third and Fourth Little Sisters. After Dad retired, he played with the ladies when a slot opened up.

In the 2000s, my sister and I would spend an afternoon a week playing with them – the nuclear family version. Dad also played in a Filipino doctors’ game that met in the evenings. They, too, had their own way of valuing mah-jongg combinations.

As with all gambling, the winners want to keep playing. And the losers want to keep playing. Sometimes the games would run into the wee hours. Then, Mom would drive home alone, head barely above the steering wheel of her Cadillac, wearing a baseball cap to hide her “little old Chinese lady” persona. I’m glad I found out about these nocturnal rides only after she had quit that practice.

After Dad’s stroke, the parents lived with Bill and me. It became clear that the game was confusing and frustrating to Dad. He preferred watching Cardinals baseball. I set up a game for Mom and me with Chinese friend Barbara and her mother. Both moms had Alzheimer’s, yet could still come up with spectacular wins on occasion.

Dad died in 2011 and Mom in 2015. I haven’t played mah-jongg since. But, etched like the patterns on the mah-jongg tiles, are my memories: Dad’s sly grin when he withholds the one piece that he knows you need and Mom’s excited cry when she draws a winning tile.

Tell me: Is there a custom that defines your family life?

8 replies on “Mom, Dad, Mah-jongg and Me”

And how many billions of people play mah-jongg?

LikeLike

Just read it again: It’s such a great essay about the little moments in life, the taken-for-granted rituals that form the strong bonds between family and friends. And in the case of mah-jongg form one of the structures of a culture.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yes, comfort and friendship and fun! Thanks for your comments,

LikeLike

Wonderful essay about Mah-jongg and so much more. You capture the ease and intimacy of the games, which must have felt like comfort in a new land. Beautiful! Thank you!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks for your editorial help, Sue!

LikeLike

Wow! So powerful! Love the sentence that memories are etched like the symbols on the tiles. Brava!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Aren’t the tiles beautiful? But then, so are playing cards! ❤️

LikeLike

Sharing parts of your lived experience is always interesting and informative. I look forward to your next shared life tale.

Our family game was and still is bridge..wish we could play it with tiles.

LikeLiked by 1 person