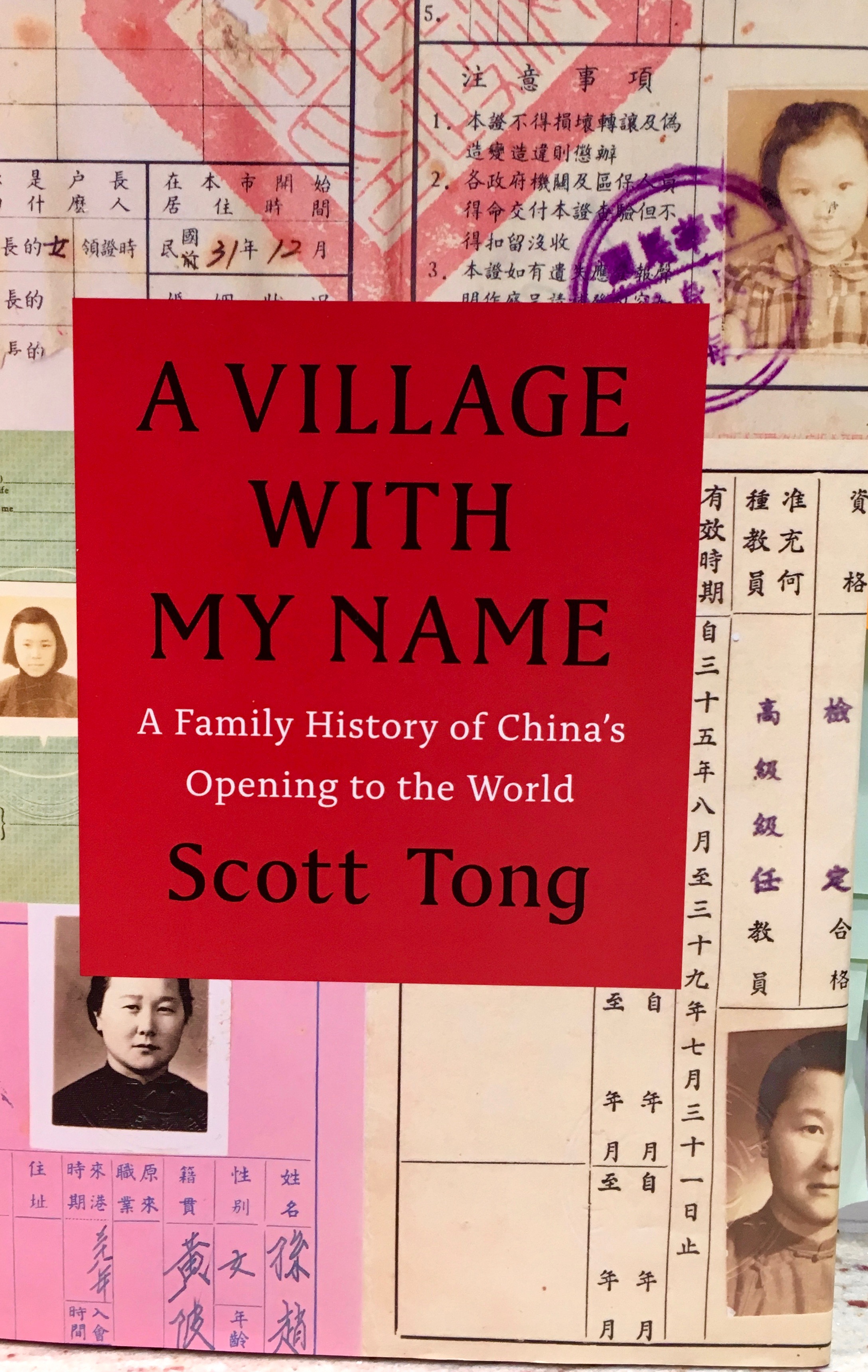

I had quite a few knowing chuckles reading Scott Tong’s account of his experiences in China in his book A Village with My Name. Like me, journalist Tong is Chinese American. Even though we grew up in Chinese homes in America, we both experienced major culture shock when we visited China as adults.

Early on, Scott talks about riding in a car to his ancestral village. “The ‘road’ we’re driving on has turned into a one-lane paved path about the width of a bike trail back home. It has the added drama of five-foot-deep irrigation ditches on either side….I try not to consider the odds of a car coming the other way, except that’s all I can think about.”

On my most recent visit to China in 2016, I was mesmerized by the death-defying traffic. A six-lane road inexplicably narrowed to two lanes. Cars, trucks, bicycles, motorized bikes, three-wheelers, electric scooters all jockeyed for road space, sometimes by going the wrong way down the sidewalk. A disabled man, one arm raised, the other on the controls of his electric wheelchair, careened catty corner across a major intersection. Every minute, I braced for some horrible accident.

Scott noted that the Chinese had always placed a premium on light skin color, especially for girls. Female TV stars were all pale. Scott’s mother was deemed “cute” because of her light skin. When Scott and his wife met their adoptive Chinese daughter for the first time, he noted, “Her skin color wasn’t ‘fairly,’ as paperwork suggested….[It] looked a shade or two darker than any of the photos.” The orphanage tried to make the child more desirable by lightening her skin in the photos.

The Chinese predilection for pale skin explains what had been always seemed to me an enigmatic comment my mom made when I was born. My dad said that her first words were, “How come she’s so dark?” And she said it not in a good way.

Scott homes in on the driving competitiveness of Chinese society: “China’s fast-forward dash for scarce resources—jobs, spouses, college spaces, affordable housing.” The winning of this race falls on the shoulders of the one child per family. (As of 2016, two children are permitted.) It can be a grueling, desperate existence. Scott’s Chinese assistant wrote in her diary “that she longed for a sibling not so much to play with as to share the harsh parental spotlight.” In my August 24, 2018 review, The Small Are Eating the Old, I talk about the grinding pressure my relatives in China, like all parents and grandparents in China, feel to give their child a competitive edge.

There were surprises on more personal levels as well. Scott’s great grandfather had studied in Japan in the early 1900s. While in Japan, he had married a Japanese woman whom he brought back to his village—quite a shock to his Chinese wife and three kids. On my first trip to China in 1977, the first of my family to go in twenty-five years, I found out that one of my uncles had four children, two with his wife and two with his paramour. You’d think my parents would have given me a heads-up.

Social interactions became more complicated as Scott embarked on his research of family history. He interviewed relatives, some long lost, still in China. Conversations with relatives, even in one’s native tongue, are sometimes difficult. As he was formulating his objections to his uncle who in effect, wanted to edit Scott’s book, he thought, “It’s hard to litigate this kind of argument in your second language.” When talking to my relatives in Chinese, I often wonder if I fully understand the point they’re making.

Besides the language, actual cultural differences stymied us as well. When is a family member “saving face” and refusing a badly needed gift? What are the rules for who should pay the restaurant tab? When are they playing you because they think you can do something for them? (I had an uncle who wanted my passport for a week so he could get some antique paintings out of China. I said no.) When are they understating out of politeness? Years ago in Hong Kong, an aunt invited my husband and me to a small, informal party for my uncle’s birthday. We showed up in street clothes for what turned out to be a full-scale, ten course banquet with dozens of guests in formal dress and in their best jade.

Many of the buildings where Scott’s relatives—and mine— grew up, worked and went to school still exist, often repurposed. His visit to his grandmother’s school reminded me of my 2016 visit to my aunt’s old convent. My aunt, mom’s older sister, entered the Helpers of the Holy Souls Catholic order in the 1930s. The European-style building smack in the middle of Shanghai is now a restaurant called “Ye Olde Station.” It has retained many of its architectural features, light fixtures and dark wood trim. I walked through it wondering if my aunt had knelt to pray in this room or had communal meals in that room or walked down that corridor.

In the book, Scott wondered about his “what if” life. “What if my dad had been the sibling left behind? What if I were the mainland cousin, driving —of all vehicles—a Buick?” I have often wondered how my life would have been if I hadn’t left China. What kind of friends would I have? What would my kid be like? Who would have been his dad? What kind of personality would I have?

When Scott was unable to track down any record of the last years of his maternal grandfather, he lamented, “I’ve waited too long to start chasing all this.” I—probably everyone—have had this feeling at some point or another. As Scott put it, “I am left with a few dozen pieces of a five hundred-piece puzzle.”

Scott put in the leg work and the brain work to track down interviews, letters and locales that helped fill out the puzzle. In my opinion, he also showed a lot of courage. To acknowledge that our relatives suffered, made bad decisions, did despicable things is not easy. I would have been tempted to put my fingers over my eyes during the emotionally uncomfortable parts, like I do during scary movies.

I think we can’t ever fully know our forebears, not even our parents, much less those relatives who are long dead. At least Scott can still ask questions of his parents and aunts and uncles. Mine are all dead. But at some point, Scott himself will be the grandfather and great grandfather. (I am already a grandma.) His kids, grandkids and great grandkids will know about where they came from and how they got there. They can catch a glimpse of what the early part of the twenty-first century was like. They will be so grateful. Hopefully, my grandsons will learn something of their ancestors through my writing as well.

I am grateful to Scott Tong also. In reading A Village With My Name, I was able to gain concrete context to my lived experience as a Chinese-American, make sense of my observations of Chinese life and even explain my discomfort with some social interactions with Chinese people. I learned about both parts of being Chinese and being American.

Tell me: One thing about your grandparents that surprised you when you first found out.

5 replies on “West Meets East: Chinese Americans Visit Mother China”

Though not as dramatic as leaving China for the other side of the world, my parents’ break with their families was wrenching enough. They left their roots in South Dakota for greener pastures working for the Federal Government in Baltimore and then Washington DC, circa 1940. My dad’s father wanted him to take over the family farm but his mother, I’m told, quietly supported his making the break. My mom’s father was often ill, and certainly ill-tempered, and it was up to her mother to provide main support for the family of seven children during the Great Depression. I gained some notoriety when, at age 10, I remarked after my grandfather’s death, ‘one good thing about funerals, there’s lots of good things to eat.’

LikeLike

If he could even get some of his dad’s stories, it would be so great.

LikeLike

I wish Max would do some of this research with his grandmother in Calcutta, while he still has the chance.

LikeLike

Don’t you wish you mom had put some of these stories on paper? Or did she?

LikeLike

I don’t remember either one of my grandfathers, except fleeting images of my dad’s dad, Roy. He died when I was 6 (Both grandmothers lived on for decades).

By the accounts of my three older siblings, Roy was a character; funny, little formal education but highly intelligent, possessing an enormous repertoire of songs and poems he could whip out at any time. He was particularly good at amusing small children.

One time when I was grown, my mother was telling about my grandfather, and happened to remark that he had left home for good at age 10.

Me: At TEN YEARS OLD???

Mom: Yes. His father died when he was eight, and he didn’t get along with his stepfather.

Me: So he ran away?

Mom: No, he just left home, with his two older brothers. I think everybody agreed it was best. They became traveling laborers, following the harvests in Oklahoma and Kansas. Later, they all worked in the oil fields. Roy was a powder monkey.

Me: A . . . powder monkey?

Mom: An expert on explosives. He said it paid better than the other jobs.

Me: Really . . . So, how did my great-grandfather die—Roy’s biological father?

Mom: He was kicked in the head by a mule.

LikeLike