“The small are eating the old.” My cousin, Yu, whose name means Jade in Chinese, said these words to me when I was in China in 2016. Yu’s point is that the older generations are sacrificing too much for the youth. (In English, I call him “cousin.” In Chinese, he is the grandson of my father’s oldest brother. Yu calls me “Auntie Ling-Ling who is related on the father’s side.”)

What? I was shocked. No society treasures its children more than the Chinese. A Chinese term for being pregnant literally means “possessing happiness” ( 有喜) Traditionally, children were responsible for the care of aging parents. The more children, the more secure one’s old age. When the government enacted its “one child policy” in the 1980s, it was bucking a mighty trend. Even today, with a hit-or-miss social insurance system for retirees, children are still many pensioners’ chief support. So, why is my cousin feeling so put upon by the young?

Since my last visit to China in 1997, almost twenty years ago, all the responsibility for childcare has shifted to grandparents. Here’s how that happened. Almost everyone who lives in an urban area has to retire by age 60 to make jobs available for younger generations. As a result, fairly young grandparents have time to do childcare. Their grown children live under very competitive situations. Housing is incredibly tight and expensive. Income inequality, once unheard of, is as high as in the United States (Harvard Business Review). Both parents must work.

The working husband and wife are each the product of the one-child policy. Their child is also an only child. Moreover, as the Chinese tend not to move from city to city, it is likely that all the grandparents are in the same town. So now, there are typically six adults (two sets of grandparents and the parents) looking after this one precious child.

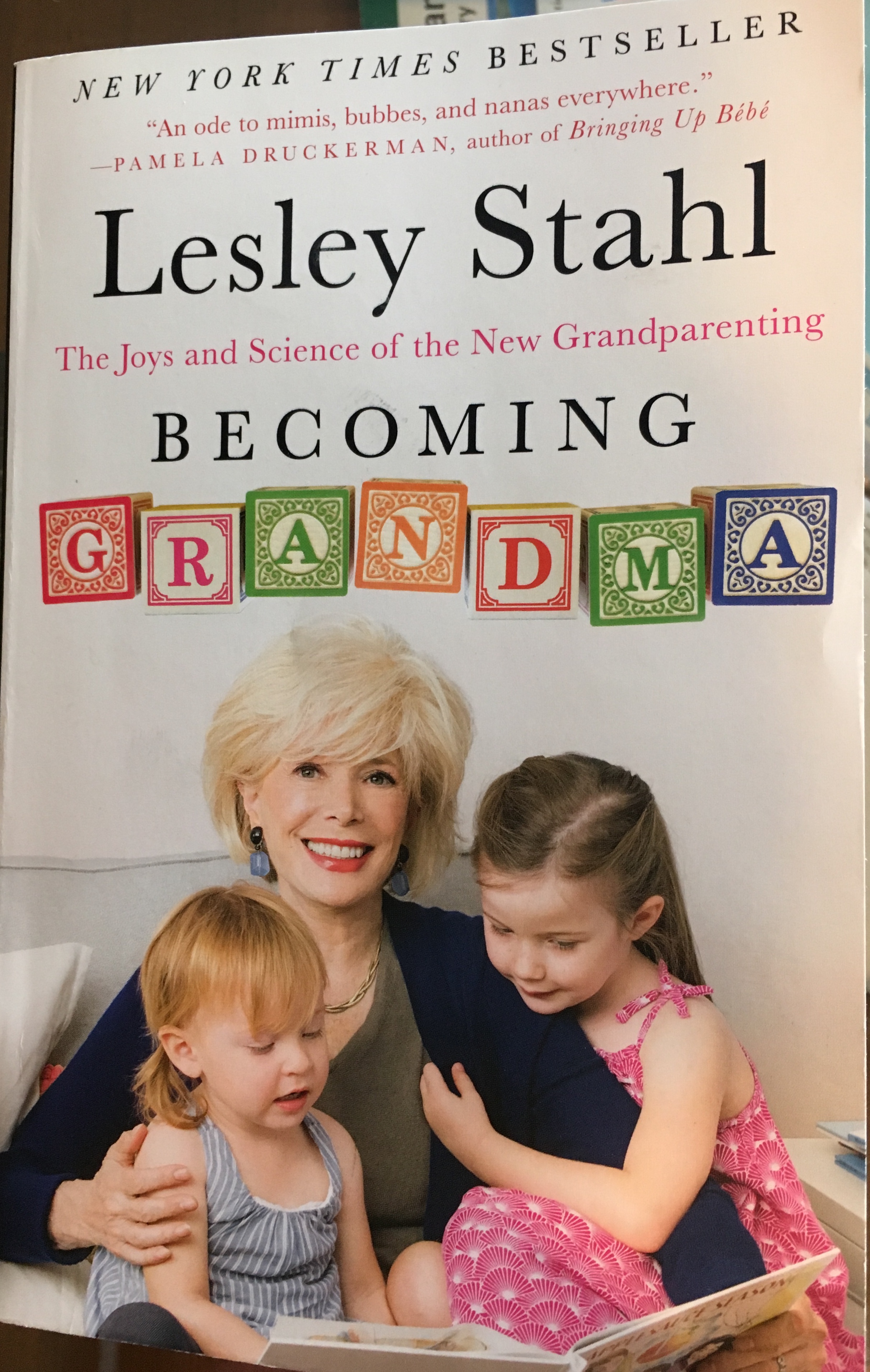

I paid more attention to Yu’s situation than I otherwise might have because I had read Lesley Stahl’s book Becoming Grandma: The Joys and Science of the New Grandparenting,” on the plane ride over. It was a birthday present from my son and daughter-in-law, the parents of my little grandson Edin.

Lesley Stahl wrote this book because she’s crazy about her grandbaby. Me too! As you can tell from my previous essay, “A Moment in Paradise,” I spent hours on the back porch just staring at the infant Edin. And since last October, Caleb is tied for the “world’s most beautiful baby” title. Besides waxing rhapsodic about her family in general, and granddaughter Jordan in particular, Stahl focused on the many permutations grandparenting takes these days.

In every category of grandparenting, I can name someone who fits. My cousin’s wife is a “granny nanny.” For several years now, she has left her home in St. Louis to live months at a time in Minnesota to care for the kids of her son and daughter-in-law, both professors. Tennis friend Jim, a grizzled Vietnam-era vet, babysits his three, soon to be four, grandkids several days and nights a week. He loves being “Papa.” An activist friend in the 1990s successfully sued her drug-addicted daughter for custody of her granddaughter. My high school friend became a grandmother after her gay son and his partner adopted a brother and sister pair of siblings.

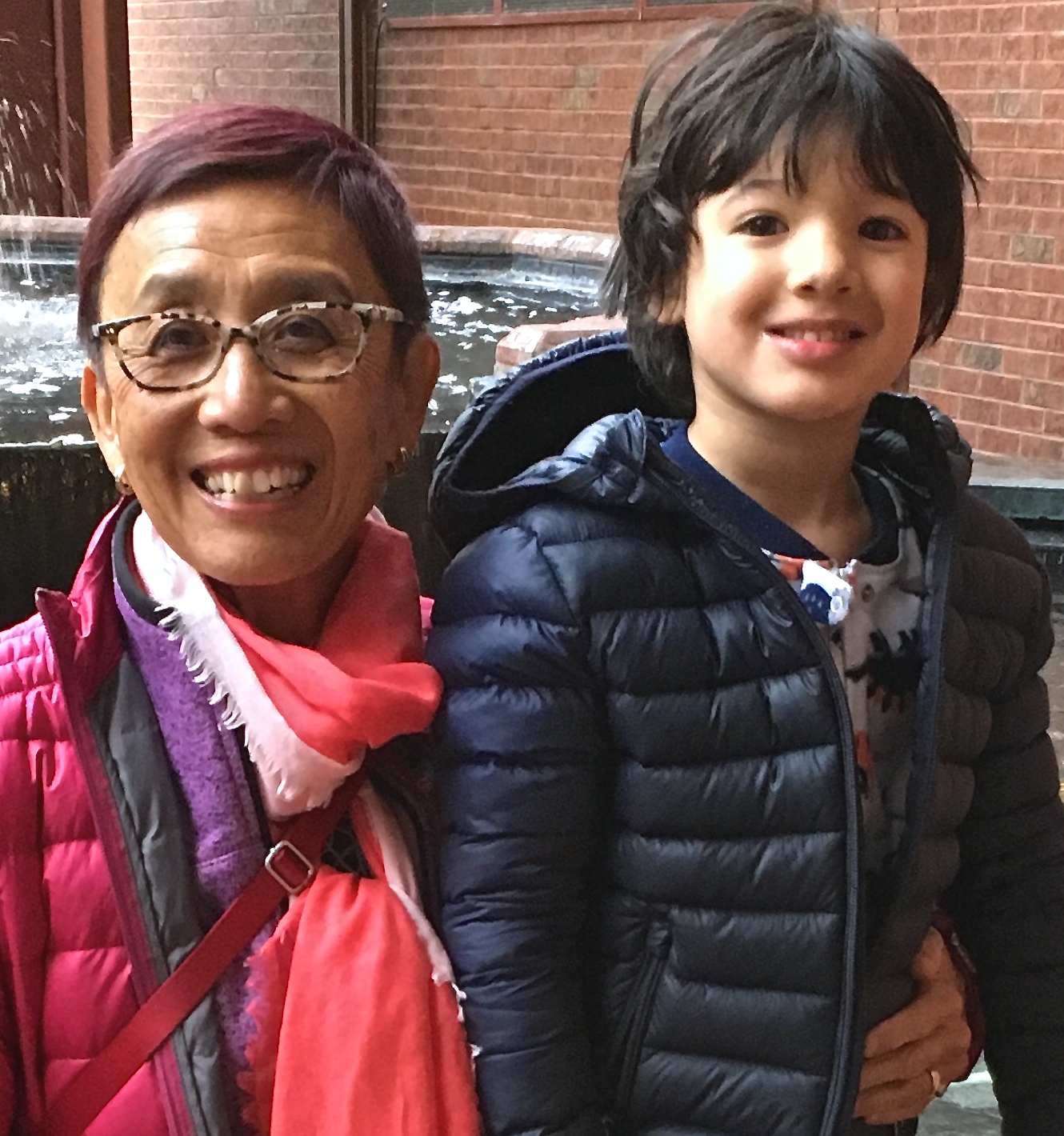

My family is part of the mix-and-match grandparents of divorce, widowhood and remarriage. Edin and Caleb have three pairs of grandparents. In addition, I am step-grandma to my husband’s seven grandchildren. Everyone I know helps with money and some level of childcare.

Stahl talks briefly about “glammas” (glamorous grandmas?) who aren’t interested in their grandkids. Some think that grandparenthood makes them old. Two years ago, I was grandmother of the bride. I usually don’t care about being old, but that felt old. Others say, “Been there. Done that.” One man described his mother’s reaction to being with the kids, “To her, they’re exhausting, boring and nerve-racking.” Stahl gives short shrift to those grandparents who are not completely bowled over by grandkids.

She glosses over the fact that some grandparents may feel a little trapped in their caretaker role. She tells the story of a woman who left her home in Ecuador to come to the US to take care of her two grandkids. For ten years! Stahl writes, “But in the end, Gramma is fulfilled, the children benefit from the love and attention, and the parents have peace of mind…. Everyone wins.” Also, she downplays the kids’ behavior. There are difficult kids, but not in Lesley Stahl’s world.

Stahl lives a privileged life. She and her husband flew to Los Angeles from New York and stayed a week and a half for the birth of their first grandchild. They redecorated their apartment to include a nursery. They rented a house for a month in Santa Barbara for a family vacation. And a lot of her anecdotal evidence comes from her wealthy, privileged friends: Mike Wallace, Morley Safer, joint chief of staff Martin Dempsey, columnist Ellen Goodman, the movers and shakers of New York and Washington. She never acknowledges that perhaps her ability to enjoy her grandchildren is related in part to her exceptional privilege.

However extravagant and extensive the help American grandparents give to their grandchildren, in most cases, they are merely helpers or boosters to the parents. This is not the case in China. Grandparents are expected, not just to kick in financially and to do babysitting, but to be the main caregivers.

I saw a hint of this before we even got to Shanghai. Bill and I had booked a week of bird watching in the western province of Sichuan. We went with a guide and a driver. Both were men in their early thirties. Each was the father of a small child. Obviously, their jobs required them to be away from home for extended periods.

They and their wives depended on their parents, especially, the wife’s mother, for childcare. It explained why, when we found some especially delicious yak jerky at roadside stand, each of them bought a kilo for their mothers-in-law.

My cousin Yu and his wife are responsible for their four-year old granddaughter Ying, whose name means smart or clever, on the weekends. Yu complained that Ying likes her other grandparents better. But he is reluctant to say anything to his son because he is worried that his childcare hours might go up. Their modest apartment is overflowing with toys. The tiny alcove that was their son’s childhood bedroom is even more crowded now that they have bought Ying a piano.

Chinese families feel a lot of pressure for their one child to keep up with the one child of the Zhangs and the Chens and the Wangs. Not just piano lessons, but English and other languages, violin and other musical instruments, classical Chinese literature, calligraphy, art and sports, anything to give their child a competitive edge.

And the lessons are not cheap. Yu told me that one piano or English lesson for children costs as much as what he pays for a semester of the seal-carving class he takes at the “elder college.” At this point he said, “The small are eating the old.”

Yu’s younger sister Lan (Orchid) has her grandson full time because he, her son and daughter-in-law and her husband all live together. This boy is ten now. She organizes all his extra-curricular activities: soccer, classical Chinese literature and martial arts. He goes home for lunch on school days. I remember getting a picture of this cute toddler and her note that she was raising him. I was surprised. I thought it was an aberration. I was wrong.

I do not want to give the impression that the actual parents are uncaring people. They pitch in mightily to raise their son or daughter. I have seen parents on a weekend with their little one in the Shanghai Art Museum using their cellphones to provide light for the child to copy an old masters painting.

In her book, Lesley Stahl assumes that the more adult attention to the children, the better for the children’s physical, emotional and intellectual development. In China, there are typically six adults totally focused on raising each child. Do those kids have an advantage?

But, what about the stress on the grandparents? Columnist Ellen Goodman said that if you’re a full-time caregiver, there’s an element of financial sacrifice and exhaustion. Well, sometimes it is exhausting. The highest number of steps I ever recorded on my iPhone, over 24,000, was the day I took care of Edin and Caleb. This was more than the steps I clocked walking to and on the Great Wall, although the Wall had many more floors. I do not entirely agree with the statement, “…with grandchildren there is no weariness that competes with the elation and joy of being with them.”

In a bit of irony, a few months before my arrival in China, the government passed a new law allowing families to have two children. Shaking his head, Yu said, “We’re able to have two children now. But I’m not sure my wife and I have the stamina for it.”

Tell me: Were your grandparents a very big part of your life? What is the easiest or hardest part about being a grandparent?

7 replies on “The Small Are Eating the Old”

I love your comment, Margaret. I’ve had some patients in similar binds. And then I feel so bad that it costs them money to see me.

LikeLike

When I think of a grandparent raising grandkids, I’m reminded of a patient I once had. She was a working class woman of very modest means who raised her daughter’s 3 children, all who were in their second decade. She was depressed by the situation she found herself in, angry with her drug-dependent dtr, alternated between feeling resentful of the g’kids and guilty because they too were victims, and she was financially strapped. She would come in for follow-up of her depression but her reality could not be meaningfully changed with medication. There were no financial resources to help her. The title of your piece aptly describes her situation.

LikeLike

When Cathy and I visited relatives in Shanghai, I was surprised at the child care duties that fell upon grandparents. Certainly, Yu felt the heavy burden of responsibility, and Ying, the cute 4-year old granddaughter, had every expectation that all the adults in the room would focus their attention toward her.

This was very different from how my father advised me to relate to his parents: “Children should be seen and not heard. Don’t speak unless spoken to.“

On the other hand, I am grateful for the times I would stay with my Granny (Mom’s mom). She would read me stories from Robinson Crusoe, spellbound me with tales from her youth in rural Brazil, and softly sing songs in Portuguese. I am very lucky to own such warm memories.

LikeLike

Interesting observations of grandparenting roles across time and cultures. My grandparents had little direct influence on me since my parents moved far away from them when I was an infant. Annual visits maintained an acquaintance but little else. Likewise, I did no care and feeding of my grandsons because I was raising a second family, with children not much older than them. I’m hoping for a second chance as my children (and grandchildren) marry and, perhaps, reproduce.

LikeLike

Great to see you and Bill with Edin and Caleb again, this time, online.

LikeLike

A great reflective piece on cultural similarities and differences in grandparenting. I grew up with my grandmother who was an amazing and intelligent woman, and spent less than 5 years in my life with my parents. I was always connected more to my grandmother and to my parents. So I wonder about the effect of a child’s being raise by a grandparent on parent-child relationship.

LikeLike

Fascinating. With six adults nurturing every child, China is going to leave the rest of the world in the dust.

LikeLike